It is known that many drug successes have originated from the use of an animal model. However, over the years several so call disasters have become apparent. In 1993, a hepatitis drug ‘Fialuridine’ resulted in five deaths and two seriously ill [1], making it the worst trial disaster on record [2]. Reports suggest that mistakes were made in the animal testing stage, resulting in these deaths. The high levels of toxicity of fialuridine was not identified in the Laboratory animals [3]. This blog will highlight the mistakes made and suggest improvements in the development of this drug.

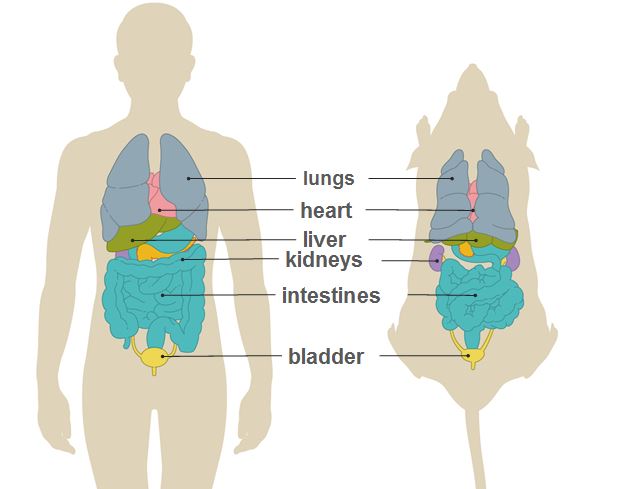

Fialuridine caused ‘hepatic, pancreatic, skeletal-muscle or nerve damage’ in humans [3]. When tested on animals these causes were not detected. Testing a drug on an animal model that is not hundred percent identical to us can be the largest mistake in this drugs development. To predict the effect and causes on an animal model, you can almost consider the results not be being completely accurate. In the toxicity test of fialuridine, the animals used were ‘mice, rats, dogs, and monkeys’ [3]. This array of animals contains similar organs and biological processes, that should react in the same way. Although none of the data collected showed any signs of toxicity immediately [4]. Therefore, using animal models as an alternative may not be as affective compared to other options [5]. However, one of the symptoms caused by fialuridine is liver failure, a mouse shares nighty percent of a human’s liver cells [6] making it highly representable of a human’s liver (Figure 1). Therefore, some signs to damage to the liver should have been detected in the mice used.

Source: Speaking of research; The Animal Model

Fialuridine was tested in a pilot study using 67 patients, then pursued to the clinical testing. After the deaths became apparent, scientists looked back on the pilot study participants and found that three people had died within six months [3]. Representing that there was a delay in the time the toxicity was identifiable or for the drug to start causing serious health problems. So, leaving an appropriate time between the trials could decrease the risk of the potential impacts. This way the full affects can be assessed before the drug is took further. Although the animals used never showed any signs of the toxicity, therefore not all lives would have been able to be saved [7]. Woodchucks (Marmota monax) were used after the disaster to retest the drug. They found the same delay in the toxicity of fialuridine in woodchucks. All woodchucks in the experiment died or were euthanized due to fialuridine [8].

To conclude, fialuridine caused fatal injuries and was impactful for all the wrong reasons. The mistakes they made were highlighted in a report after the trials and have changed the way we conduct clinical trials [2]. It is important when these disasters in drug development happen, rectifying the process is essential for the prevention of other lives being lost. Alternatives may have been more beneficial to the testing of this drug, rather then animals. The most substantial mistake in this trial was the time period between each trial. Eventually the pilot studies and animal testing stage would have shown signs of toxicity.

References

[1] Manning, F.J. and Swartz, M. (1995). Review of the fialuridine (FIAU) clinical trials. National Academies.

[2] Thompson, L. (1994) The Cure that Killed. Available at: https://www.discovermagazine.com /health/the-cure-that-killed [Accessed 21 November 2019]

[3] McKenzie, R., Fried, M.W., Sallie, R., Conjeevaram, H., Di Bisceglie, A.M., Park, Y., Savarese, B., Kleiner, D., Tsokos, M., Luciano, C. and Pruett, T. (1995) Hepatic failure and lactic acidosis due to fialuridine (FIAU), an investigational nucleoside analogue for chronic hepatitis B. New England Journal of Medicine, 333(17), pp.1099-1105.

[4] Straus, S.E., (2018). Unanticipated risk in clinical research. In Principles and Practice of Clinical Research (pp. 141-159). Academic Press.

[5] Rowan, A.N. and Goldberg, A.M., (1985). Perspectives on alternatives to current animal testing techniques in preclinical toxicology. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 25(1), pp.225-247

[6] PLOS. (2014) Mouse model would have predicted toxicity of drug that killed 5 in 1993 clinical trial. ScienceDaily. Available at: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/04/140415181321.htm [Accessed 21 November 2019]

[7] Xu, D., Nishimura, T., Nishimura, S., Zhang, H., Zheng, M., Guo, Y.Y., Masek, M., Michie, S.A., Glenn, J. and Peltz, G., (2014). Fialuridine induces acute liver failure in chimeric TK-NOG mice: a model for detecting hepatic drug toxicity prior to human testing. PLoS medicine, 11(4), p.e1001628.

[8] Tennant, B.C., Baldwin, B.H., Graham, L.A., Ascenzi, M.A., Hornbuckle, W.E., Rowland, P.H., Tochkov, I.A., Yeager, A.E., Erb, H.N., Colacino, J.M. and Lopez, C., (1998). Antiviral activity and toxicity of fialuridine in the woodchuck model of hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology, 28(1), pp.179-191.